Information

Version: B | 1.3 (2022-07-29)

WelfareScore | farm

Condensed assessment of the species' likelihood and potential for good fish welfare in aquaculture, based on ethological findings for 10 crucial criteria.

- Li = Likelihood that the individuals of the species experience good welfare under minimal farming conditions

- Po = Potential of the individuals of the species to experience good welfare under high-standard farming conditions

- Ce = Certainty of our findings in Likelihood and Potential

WelfareScore = Sum of criteria scoring "High" (max. 10)

General remarks

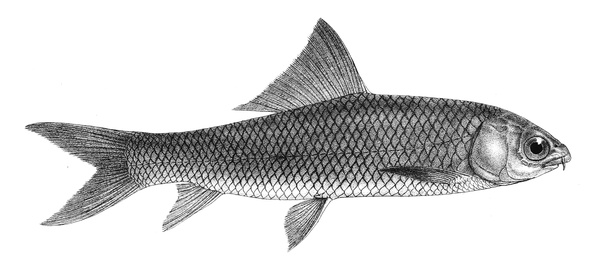

Cirrhinus mrigala is – besides Labeo catla and L. rohita – one of the three Indian major carps cultivated widely in Southeast Asian countries. This species can be found in fresh waters of northern India, Bangladesh, Burma, and Pakistan and has been introduced into waters of other parts of India and adjacent countries – including China – and to parts of Asia as well as Europe. Despite that, there is limited information about this species in natural conditions, especially about substrate and aggregation needs. C. mrigala is often raised in polyculture systems with other carps, and structures such as bamboo poles can be used as periphyton substrate in these systems, reducing competition for food between carps with different feeding habits. This species has a narrow range in food variety. As a bottom feeder, complete harvesting of C. mrigala is possible only through draining, and such difficulty makes this species the least preferred one among the three Indian major carps for farmers. Moreover, its entire life cycle is closed in captivity, but apparently it is still necessary to induce the reproduction by hormonal manipulation. Information about adults under farming conditions is scarce, probably because this species is sold before reaching maturity. C. mrigala is mostly sold fresh in local markets, but it is a common practice that fishes are harvested, packed with crushed ice at a ratio of 1:1 in rectangular plastic crates, and transported – sometimes for long distances – to be sold as fresh as possible. Thus, post-harvest processing of this species is almost non-existent. Further research is needed on the stunning and slaughter process, besides the stress response of this species.

1 Home range

Many species traverse in a limited horizontal space (even if just for a certain period of time per year); the home range may be described as a species' understanding of its environment (i.e., its cognitive map) for the most important resources it needs access to.

What is the probability of providing the species' whole home range in captivity?

It is unclear for minimal and high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

2 Depth range

Given the availability of resources (food, shelter) or the need to avoid predators, species spend their time within a certain depth range.

What is the probability of providing the species' whole depth range in captivity?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

3 Migration

Some species undergo seasonal changes of environments for different purposes (feeding, spawning, etc.), and to move there, they migrate for more or less extensive distances.

What is the probability of providing farming conditions that are compatible with the migrating or habitat-changing behaviour of the species?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

4 Reproduction

A species reproduces at a certain age, season, and sex ratio and possibly involving courtship rituals.

What is the probability of the species reproducing naturally in captivity without manipulation of theses circumstances?

It is low for minimal and high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

5 Aggregation

Species differ in the way they co-exist with conspecifics or other species from being solitary to aggregating unstructured, casually roaming in shoals or closely coordinating in schools of varying densities.

What is the probability of providing farming conditions that are compatible with the aggregation behaviour of the species?

It is unclear for minimal and high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

6 Aggression

There is a range of adverse reactions in species, spanning from being relatively indifferent towards others to defending valuable resources (e.g., food, territory, mates) to actively attacking opponents.

What is the probability of the species being non-aggressive and non-territorial in captivity?

It is unclear for minimal and high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a low amount of evidence.

7 Substrate

Depending on where in the water column the species lives, it differs in interacting with or relying on various substrates for feeding or covering purposes (e.g., plants, rocks and stones, sand and mud, turbidity).

What is the probability of providing the species' substrate and shelter needs in captivity?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

8 Stress

Farming involves subjecting the species to diverse procedures (e.g., handling, air exposure, short-term confinement, short-term crowding, transport), sudden parameter changes or repeated disturbances (e.g., husbandry, size-grading).

What is the probability of the species not being stressed?

It is unclear for minimal and high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a low amount of evidence.

9 Malformations

Deformities that – in contrast to diseases – are commonly irreversible may indicate sub-optimal rearing conditions (e.g., mechanical stress during hatching and rearing, environmental factors unless mentioned in crit. 3, aquatic pollutants, nutritional deficiencies) or a general incompatibility of the species with being farmed.

What is the probability of the species being malformed rarely?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a medium amount of evidence.

10 Slaughter

The cornerstone for a humane treatment is that slaughter a) immediately follows stunning (i.e., while the individual is unconscious), b) happens according to a clear and reproducible set of instructions verified under farming conditions, and c) avoids pain, suffering, and distress.

What is the probability of the species being slaughtered according to a humane slaughter protocol?

It is low for minimal farming conditions. It is medium for high-standard farming conditions. Our conclusion is based on a low amount of evidence.

Side note: Domestication

Teletchea and Fontaine introduced 5 domestication levels illustrating how far species are from having their life cycle closed in captivity without wild input, how long they have been reared in captivity, and whether breeding programmes are in place.

What is the species’ domestication level?

DOMESTICATION LEVEL 4 31, level 5 being fully domesticated.

Side note: Forage fish in the feed

450-1,000 milliard wild-caught fishes end up being processed into fish meal and fish oil each year which contributes to overfishing and represents enormous suffering. There is a broad range of feeding types within species reared in captivity.

To what degree may fish meal and fish oil based on forage fish be replaced by non-forage fishery components (e.g., poultry blood meal) or sustainable sources (e.g., soybean cake)?

All age classes: WILD: detritivorous 1, bottom feeder 1 32 and omnivorous 32. FARM: fish meal may be partly* 5 to mostly* 7 replaced by sustainable sources. LAB: fish oil 33 34 and fish meal may be partly* replaced by sustainable sources, especially when the diet is supplemented with 1,000 phytase activity units/kg 34.

*partly = <51% – mostly = 51-99% – completely = 100%

Glossary

DOMESTICATION LEVEL 4 = entire life cycle closed in captivity without wild inputs 31

FARM = setting in farming environment or under conditions simulating farming environment in terms of size of facility or number of individuals

FRY = larvae from external feeding on, for details ➝ Findings 10.1 Ontogenetic development

IND = individuals

JUVENILES = fully developed but immature individuals, for details ➝ Findings 10.1 Ontogenetic development

LAB = setting in laboratory environment

LARVAE = hatching to mouth opening, for details ➝ Findings 10.1 Ontogenetic development

PHOTOPERIOD = duration of daylight

POTAMODROMOUS = migrating within fresh water

SPAWNERS = adults during the spawning season; in farms: adults that are kept as broodstock

WILD = setting in the wild

Bibliography

2 Rai, Sunila, Yang Yi, Md Abdul Wahab, Amrit N Bart, and James S Diana. 2008. Comparison of rice straw and bamboo stick substrates in periphyton‐based carp polyculture systems. Aquaculture Research 39: 464–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2008.01898.x.

3 Rai, S., Y. Yi, Md. Wahab, A. Bart, and J.S. Diana. 2010. Comparison of the Growth and Production of Carps in Polyculture Ponds with Supplemental Feed using Rice Straw and Kanchi as Substrates. Our Nature 8: 92–105. https://doi.org/10.3126/on.v8i1.4316.

4 Azim, M.E., M.M. Rahaman, M.A. Wahab, T. Asaeda, D. C. Little, and M.C.J. Verdegem. 2004. Periphyton-based pond polyculture system: a bioeconomic comparison of on-farm and on-station trials. Aquaculture 242: 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.09.008.

5 Parveen, S., I. Ahmed, A. Mateen, M. Hameed, and F. Rasool. 2012. Substitution of animal protein with plant protein fed to Labeo rohita and Cirrhinus mrigala and its effect on growth and carcass composition. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences 49: 569–575.

6 Sahu, P. K., J. K. Jena, P. C. Das, S. Mondal, and R. Das. 2007. Production performance of Labeo calbasu (Hamilton) in polyculture with three Indian major carps Catla catla (Hamilton), Labeo rohita (Hamilton) and Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton) with provision of fertilizers, feed and periphytic substrate as varied inputs. Aquaculture 262: 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.11.016.

7 Karim, Aasia, and Mohammad Shoaib. 2019. Influence of Corn Gluten Meal on Growth Parameters and Carcass Composition of Indian Major Carps (Catla catla, Labeo rohita and Cirhinus mrigala). Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 19: 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4194/1303-2712-v19_1_01.

8 Mohanty, R. K. 2004. Density-dependent growth performance of Indian major carps in rainwater reservoirs. Journal of Applied Ichthyology 20: 123–127. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0426.2003.00532.x.

9 Sarkar, S. K., A. Saha, S. Dasgupta, S. Nandi, D. K. Verma, P. Routray, C. Devaraj, et al. 2010. Photothermal manipulation of reproduction in Indian major carp: a step forward for off-season breeding and seed production. Current Science (00113891) 99: 960–964.

10 Sarang, N., L. L. Sharma, and V. P. Saini. 2009. Age, growth and harvestable size of Cirrhinus mrigala from the Jawahar Sagar Dam, Rajasthan, India. Indian Journal of Fisheries 56: 215–218.

11 Chandrvanshi, R., R. Uraon, N. Sarang, and H. K. Vardia. 2019. Studies on length-weight relationship (LWR) and condition factor of Labeo rohita and Cirrhinus mrigala in sutiapat reservoir, Kabirdham, Chhattisgarh, India. Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 7: 420–424.

12 Mirza, Z. S., M. N. Javed, and Muhammad Ramzan Mirza. 2006. Fishes of River Jhelum from Mangla to Jalalpur near Head Rasool. Biologia (Pakistan) 52: 215–227.

13 Rana, N., and S. Jain. 2018. DNA Quantification of Wild and Cultured Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton, 1822) Collected from Different Sites of Western Uttar Pradesh, India. International Journal of Zoological Investigations 4: 181–185. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.19464.67847.

14 Gupta, N., S. P. S. Dutta, and C. Shekhar. 2016. Deformities in Cirrhinus mrigala (Ham.Buch.) cultured in fresh water fish ponds in Jammu district,Jammu and Kashmir State, India. Environment Conservation Journal 17: 73–84. https://doi.org/10.36953/ECJ.2016.171209.

15 Dutta, S. P. S., D. Slathia, G. Chander, and H. Kumar. 2011. Anomalies in Cirrhinus mrigala, a commercially important freshwater food fish, from Gurdaspur district of Punjab. The Bioscan 6: 405–411.

16 Das, S. P., D. Bej, S. Swain, J. K. Jena, and P. Das. 2012. Relative age and growth of indian major carp, Cirrhinus mrigala, from peninsular rivers of India 20: 35–43.

17 Ujjania, N.C., and S. Nandita. 2020. Age structure, growth rate and exploitation pattern of Indian major carp (Cirrhinus mrigala, Ham. 1822) from Vallabhsagar reservoir (Gujarat). Indian Journal of Experimental Biology 58: 498–501.

18 Sultana, N., M. A. Chowdhury, and M. Shahnawaj. 2020. Seasonal movement of fish species of Rajshahi and Khulna division in Bangladesh. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 8: 639–645.

19 Das, T., A. K. Pal, S. K. Chakraborty, S. M. Manush, R. S. Dalvi, S. K. Apte, N. P. Sahu, and K. Baruah. 2009. Biochemical and stress responses of rohu Labeo rohita and mrigal Cirrhinus mrigala in relation to acclimation temperatures. Journal of Fish Biology 74: 1487–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2009.02216.x.

20 Rokade, P., R. M. Ganeshwade, and S. R. Somwane. 2006. A comparative account on the induced breeding of major carp Cirrhina mrigala by pituitary extract and ovaprim. Journal of Environmental Biology 27: 309–310.

21 Dwivedi, A. C., S. Khan, and P. Mayank. 2017. Stressors altering the size and age of Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton, 1822) from the Ghaghara River, India. Oceanography & Fisheries 4: 1–4. https://doi.org/10.19080/OFOAJ.2017.04.555642.

22 Jhingran, V. G., and H. A. Khan. 1979. Synopsis of biological data on the mrigal Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton, 1822). FAO Fisheries Synopsis 120. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

23 Das, A. K. 1972. Breeding of an Indian carp (Cirrhana mrigala) under different environmental temperatures. Biochemical Journal 128: 40P-40P. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj1280040Pc.

24 Kaul, M., and K.K. Rishi. 1986. Induced spawning of the Indian major carp, Cirrhina mrigala (Ham.), with LH-RH analogue or pimozide. Aquaculture 54: 45–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(86)90253-X.

25 Sharma, J., S. Kumar, and R. Chakrabarti. 2004. Optimization of stocking density of Labeo rohita and Cirrhinus mrigala spawn in relation to water quality, survival and growth under recirculating system. Indian Journal of Animal Sciences 74: 686–689.

26 Chatterjee, Nirupama, Asim K Pal, Tilak Das, Manush S Mohammed, Kamal Sarma, Gudipati Venkateshwarlu, and Subhas C Mukherjee. 2006. Secondary stress responses in Indian major carps Labeo rohita (Hamilton), Catla catla (Hamilton) and Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton) fry to increasing packing densities. Aquaculture Research 37: 472–476. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2006.01469.x.

27 Rath, S.C., S.D. Gupta, and S. Dasgupta. 1995. Common embryonic abnormalities of Indian major carps bred in indoor hatchery systems. Journal of Aquaculture in the Tropics 10: 193–199.

28 Ayyappan, S. Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme. Cirrhinus mrigala. Rome: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department.

29 Retter, Karina, Karl-Heinz Esser, Matthias Lüpke, John Hellmann, Dieter Steinhagen, and Verena Jung-Schroers. 2018. Stunning of common carp: Results from a field and a laboratory study. BMC Veterinary Research 14: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1530-0.

30 Rahmanifarah, K., B. Shabanpour, and A. Sattari. 2011. Effects of Clove Oil on Behavior and Flesh Quality of Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) in Comparison with Pre-slaughter CO2 Stunning, Chilling and Asphyxia. Turkish Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 11: 139–147.

31 Teletchea, Fabrice, and Pascal Fontaine. 2012. Levels of domestication in fish: implications for the sustainable future of aquaculture. Fish and Fisheries 15: 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12006.

32 Mishra, S. P. 2020. Seasonal variation in gut contents of indian major carp, Cirrhinus mrigala from Meeranpur lake, India. International Journal of Biological Innovations 2: 202–208. https://doi.org/10.46505/IJBI.2020.2216.

33 Singh, S. K., M. A. Rather, S. C. Mandal, P. Das, N. Pawar, Y. J. Singh, and S. A. Dar. 2012. Effects of Dietary Fish Oil Substitution with Palm Oil on Growth, Survival, and Muscle Proximate Composition of Cirrhinus mrigala (Hamilton, 1822). The Israeli Journal of Aquaculture - Bamidgeh 809. https://doi.org/10.46989/001c.20607.

34 Hussain, S. M., T. Hameed, M. Afzal, A. Javid, N. Aslam, S. Z. H. Shah, M. Hussain, M. Z. H. Arsalan, and M. M. Shahzad. 2017. Growth Performance and Nutrient Digestibility of Cirrhinus mrigala Fingerlings Fed Phytase Supplemented Sunflower Meal Based Diet. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 49: 1713–1724. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjz/2017.49.5.1713.1724.